Over the past couple of weeks, we’ve been bombarded by news beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. On July 11, Sir Richard Branson and five others traveled 80km aboard the Virgin Galactic — a trip that took about an hour and a half. Just days later, Jeff Bezos blasted off on the Blue Origin with two additional passengers. Elon Musk is not far behind.

While some people are applauding these new journeys into space, the billionaire space race is drawing its fair share of criticism — and not without reason.

While COVID-19 continues to ravage communities across the world, the ultra-rich are funding unnecessary joy rides fed by their egos. Amazon is known for its disregard for safe working conditions and low wages, yet after Bezos’ trip into space, he said, “I want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer because you guys paid for all of this. Seriously, for every Amazon customer out there and every Amazon employee, thank you from the bottom of my heart very much. It's very appreciated.” All of this comes on the heels of reporting by ProPublica showing how wealthy Americans like Bezos and Musk avoid paying taxes.

Now is the time for tourism professionals to draw a line in the sand and say that space travel is, in fact, not tourism at all.

So, yes, people are rightly salty about this space race. And those working in the tourism industry, in particular, should be wary of how the narrative of space travel unfolds.

Not All Travel is Created Equal

On March 11, 2020, The Hamilton Spectator published a political cartoon by Graeme McKay with a “recession” tidal wave looming over a “COVID-19” tidal wave looming over a Canadian city with a speech balloon that says, “Be sure to wash your hands and all will be well.” Over the last year and a half, this cartoon has gone wildly viral. An iteration of this cartoon now widely cited has a “climate change” wave looming over the “recession” tidal wave and a “biodiversity loss” wave looming over the three smaller waves — which still loom over the city.

Branson, Bezos, and Musk seem to think the solution to the problem depicted by McKay is simply to fly away from it. In fact, Bezos implied as much: “We need to take all heavy industry, all polluting industry and move it into space, and keep Earth as this beautiful gem of a planet that it is,” he said during an interview with MSNBC. This apparently “reinforces (his) commitment to climate change.”

So, Bezos is willing to travel to and muck up space so he can “save” Earth to the detriment of the vast majority of people who will never come anywhere close to being able to pay the price. Where have we heard that white savior story before?

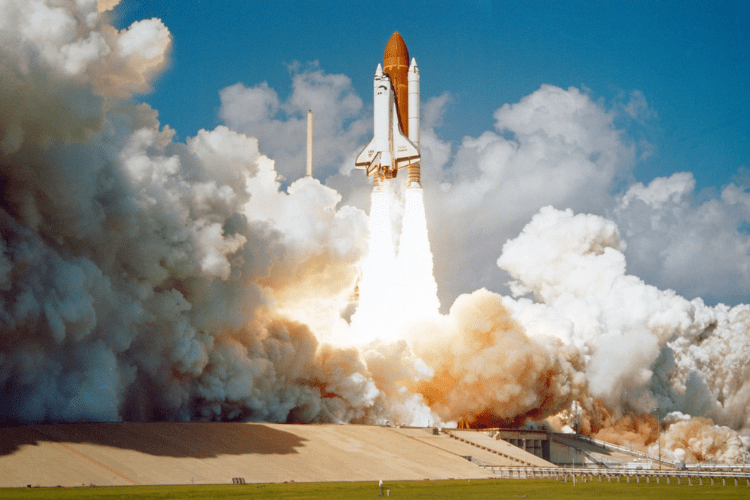

Not only does space travel come at a high financial cost, but the environmental footprint is massive: To get to space, one rocket launch produces up to 300 tons of carbon dioxide (for approximately four passengers), in comparison to one long-haul commercial flight, which produces one to three tons of carbon dioxide per passenger. And while the number of trips into space is infinitesimal compared to the 100,000 commercial airline flights that take off every day (at least for the time being), rockets emit emissions right into the upper atmosphere and the direct impact rockets have on the ozone layer is devastating.

This is not to say that commercial flying should be handed a free pass for its environmental impact. Not at all. But what is missing from this equation is a bigger-picture examination of each scenario.

Rocket ship passengers pay a ridiculous amount of money to reach the outer limits of the atmosphere so they can see Earth from above, float around weightless for a few minutes, and say they’ve ticked that item off their bucket list. The flight is the purpose, not unlike the flights to nowhere that sold out in 2020. In addition to the company that collects the fee, the only beneficiary of the experience is the traveler.

Commercial flight passengers, however, are part of a larger travel ecosystem that has the potential to positively impact the natural environment, local communities, and wildlife. Travelers may be interacting with and learning from the people they meet, participating in citizen science projects, actively supporting sustainable development, and infusing local economies with financial benefits. In this case, the flight is a tool that can be (but is not always) used to support and benefit a wider net of people, relationships, cultural heritage, the environment, research, and biodiversity.

Redefining — and Reclaiming — the Tourism Narrative

Two flights, two very different ripple effects of impact … and yet both trips are defined as tourism.

“Tourism” is defined as “travel for pleasure or business” and “the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists,” especially for commercial purposes. Under this definition, calling these recent jaunts into the atmosphere “space tourism,” or human space travel for recreational purposes, is accurate.

But for professionals in the tourism industry, use of the word “tourism” in this context can have damaging consequences.

Over the past several years — and since early 2020, in particular — there has been a movement within the tourism industry to create models of operation that minimize negative impact and maximize positive impact when people travel. It is beginning to acknowledge and correct its traveler-centered focus, prioritizing the needs and desires of people living in the destinations travelers visit instead. A number of destinations, companies, and accommodations have declared a climate emergency, and many are also leaning into regenerative practices.

For professionals in the tourism industry, use of the word “tourism” in this context can have damaging consequences.

The forward-focused Future of Tourism Coalition has even outlined 13 guiding principles to, well, guide the future of tourism. These include maximizing the retention of tourism revenue within destination communities, reducing the industry’s burdens, mitigating climate impacts, operating business responsibly, and protecting the sense of place by retaining and enhancing destinations’ identity and distinctiveness.

This is a higher quality, more mindful, more equatable, and more intentional model of tourism being shaped and delivered by those working day in and day out in the industry. The definition of tourism, based on this day-to-day work and effort, is travel for business or pleasure that attempts to maximize value for and minimize harm to biodiversity, the environment, and people living in destination communities.

Space “tourism” does none of these things. In fact, it is the antithesis to this definition.

Is the tourism industry as it currently exists perfect? No, absolutely not. But the industry is evolving, and with that evolution comes the need to examine the language we use to describe it.

If “climate grief” and “Zoom fatigue” can enter our lexicon to describe the world we live in, then it’s time to introduce a term that describes activities done simply to please one’s ego to the detriment of other people, the environment, and regenerative efforts.

Tourism professionals actively working to create a safer, more equitable, and less traveler-focused model have the most at stake for introducing and using such terminology for two reasons: First, many activities that fall under this purview are often done in the travel context. This includes things like climbing Uluru before it was closed to the public or swimming with dolphins.

The industry is evolving, and with that evolution comes the need to examine the language we use to describe it.

Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, those in the industry are attempting to redefine and deliver on this new, evolved definition of tourism. However, when people outside this inner circle hear terminology like “space tourism,” it reinforces an outdated, colonial, dangerous, and harmful concept of what tourism is.

It is impossible for the tourism industry to move forward in an active, meaningful, and mindful way if it attempts to do so in a silo. “Travel” means moving from one place to another, typically over a given physical distance. So, yes, space travel is travel. But now is the time for tourism professionals to draw a line in the sand and say that space travel is, in fact, not tourism at all.

Language Matters

The climate is changing. Consumer preferences are changing. Tourism is changing as well.

And as the industry evolves, it must be proactive in adopting new language that adequately describes the ecosystem in which it operates. This has been the case with words like "overtourism" and "greenwashing".

Now, as Branson, Bezos, and Musk stand at the brink of claiming a word the tourism industry has worked so hard to redefine and protect, it’s time to stand up and be very clear in stating that what they’re endorsing isn’t a form of tourism at all.