Having driven the U.S. interstate system through the Midwest countless times, my partner and I decided on a different strategy for our summer holiday: We took five days to drive from my parents’ home in West Central Wisconsin to a lakeside rental in Northeast Oklahoma for a family reunion by booking quirky accommodations, then strung them together with “blue highways” — the rural routes indicated by blue lines on a printed map.

This part of the country is known for being fairly flat and “boring,” to quote many people who have visited this part of the country. My impression, though, as we passed farm after farm, fell on a scale that started at horror and passed through disgust on the way to sadness.

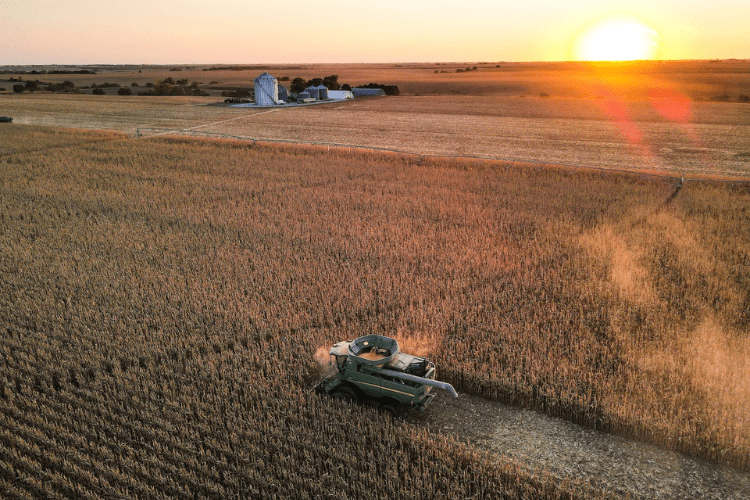

For hundreds of miles, we passed monocultural farmland — usually soybeans or corn — stretching to the horizon and beyond. Interspersed with the crops were feedlots heaving with filthy cows, stripped of anything left to graze. Massive silos sat next to the giant cattle barns and chicken coops, many of which, I imagine, are filled with feed harvested from the farms grown for the livestock.

It is the manifestation of depletion — the circular degradation of land.

Tucked among these fields and farms were singular homes — presumably where the farmers lived — all of which were surrounded by trees. These homesteads on their tree-packed plots stuck out to me. Have they planted trees for privacy, or to block out the sound from passing traffic? Is it shade from the harsh sun — a cool retreat against a warming world?

Do they realize the value of trees, of which they stripped the land surrounding their homes to build their farms? Honestly, I can hardly blame the farmers. The agricultural industrial complex has deep roots in the “flyover states.”

I appreciated our drive, the gentle rolling hills served with a new perspective, but for hundreds of miles, I couldn’t help but feel that the land was dead. People moved through this space isolated in their air conditioned vehicles. In three days, we saw only three deer and no other wildlife beyond the occasional roadkill racoon. The only other living creatures we saw were the thousands of cattle crammed into tiny outdoor pens, their lives defined by misery from birth.

This drive, instead of filling me with a sense of adventure, pushed a question through my mind on repeat: What have we done to our world?

Within society at large, and in the United States in particular, we have been fed a myth that bigger is better and more should be the end goal. That purchasing power is ideal. That consumerism and capitalism equals abundance.

But this mindset and belief system — and the never-ending urge to pursue this ideal — is a downward spiral that traps society into increasingly more constricted definitions of freedom, wealth, and happiness. We can’t escape the chase, and instead seek more “stuff” to “keep up,” pushing us even further away from the relationships and connections that could actually result in a healthier, safer, more fulfilling life.

Every time I visit America, this disconnection becomes more apparent. The grocery stores keep getting bigger. The portions overflow plates. The ease and speed with which any item can arrive on a doorstep seems to get easier and faster with each passing day. The air conditioners blast frigid air.

Oversized vehicles packed with the latest technology shield passengers from anything resembling the outside world. People jump on the interstate highway and have no idea they’re passing by these mega-farms that have stripped the land away, but they’ll happily stop for a quick burger from the fast food drive-thru window — the closest connection they have to the origins of their food.

These things are all considered signs of progress.

Yet, driving along the blue highways, I couldn’t help but feel like the opposite was true: What would we really lose by having fewer choices? What would it feel like to be more connected to the food we ate and the material possessions we owned? What if, instead of planting trees around our homes, we didn’t decimate the land of trees to begin with? What if being a bit uncomfortable was considered a virtue instead of an inconvenience?

What if we had to think more carefully about our choices, be patient, and not always get what we wanted right away? What if we knew how to differentiate between needs and wants? What if, instead of dollars and gadgets, we counted jokes that made us laugh, stars in the sky, and butterflies in the garden?

What would we really lose by living smaller? Perhaps we’d find abundance not from gaining more, but by giving things up — money, power, followers, “stuff” — that keep us from fully recognizing and appreciating the value of what we have.

As we made our way down America’s spine, these thoughts reflected upon similar ones I’ve been hearing through my work in tourism. There have been some whisperings of degrowth — an intention to cut production and consumption in order to preserve environmental integrity and ensure the holistic wellbeing of people — and yet, most people seem fearful of imagining what true degrowth in tourism might look like, let alone what it might mean to truly press the “reset” button: Less flying and fewer rewards programs; more emphasis on journeys instead of destinations. A willingness not only to dump the bucket list but also being willing to accept that tourists don’t belong in all places. Fewer multinational companies and more hyper-local operators. Less emphasis on certifications as a means of validation and more emphasis on generational knowledge, lived experience, and local solutions. Saying “no” when people or the planet suffer at the hands of profit; treating “yes” as a gift.

These are only a few of my own fleeting thoughts. I don’t claim to know the best way forward, but I also don’t feel like I hear enough conversation that truly challenges the harmful status quo under which the tourism industry currently operates.

I know it’s nearly impossible to stuff the genie back in the bottle. Convincing anyone that they may need to give up aspects of their lives that are comfortable is a big task. Changing mindsets en route to changing society — and each of the industries and sectors operating within it — as it currently operates almost doesn’t seem feasible.

And yet, journeying mile after mile and hour after hour along the blue highways and the seemingly sickly landscape that stretched far beyond, I couldn’t convince myself that this is the best we could do. That this is the world we want to live, play, and work in.

This can’t possibly be the best life we can live, and the world in which we want to inhabit. I, for one, believe something needs to change.

Despite what we’ve been told, perhaps it isn’t the person who has the most stuff who wins. Rather, maybe the real winner is the person who gave generously, listened intuitively, felt deeply, learned willingly, slowed intentionally, and embraced their smallness — and, therefore, their greatness — in a world meant to overflow with vitality and vibrancy … but didn’t need or desire the validation of “winner” at all.

Don't let a single "aha" moment pass you by ...

Subscribe to the biweekly Rooted newsletter so you never miss an article.